K-mer analysis with python

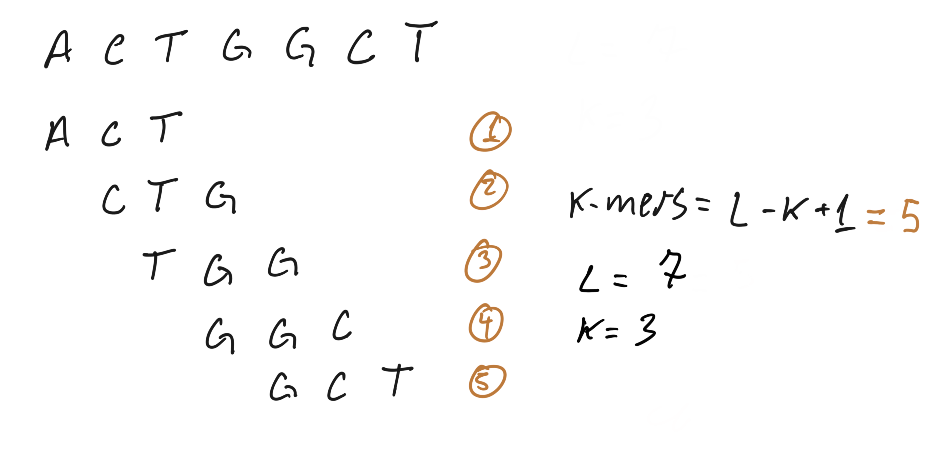

K-mers are n-gram applied to computational genomics, the basic idea is to use subsequences of DNA to answer biological questions, when dealing with software that perform k-mer analysis we often take it in the context of all possible subsequences of length K, it’s one of those things that is easily grasped by a ugly hand draw:

Here is a simple implementation of a k-mer count function in python, this require a lot of memory to run and can not be used in real life with NGS data (unless you have tons of memory to spare), but works fine for understanding the idea of k-mer counting.

def count_kmers(sequence, k_size):

data = {}

size = len(sequence)

for i in range(size - k_size + 1):

kmer = sequence[i: i + k_size]

try:

data[kmer] += 1

except KeyError:

data[kmer] = 1

return data

count_kmers("CTGACTGACTGACTGTA", 3)

output:

{'CTG': 4, 'TGA': 3, 'GAC': 3, 'ACT': 3, 'TGT': 1, 'GTA': 1}

k-mer analysis has many uses in bioinformatics, to quote a few:

- genome assembly ( spades )

- taxonomy classification ( kraken )

- genome comparison (minhash)

- genome analysis ( jellyfish + genomescope )

- sequence data compression

With this broader usage you may wonder what make k-mers so interesting? The short answer is that k-mers are computationally cheap to produce, sort, count and compare, while aligners for example, are expensive and need to deal with all sort of ambiguities like mismatches and gaps.

But how can we extract useful information from such small pieces of DNA?

The size required for a k-mer will change broadly between applications, for

taxonomy classification a large k may carry information at species level, while

a small k will give information at a higher rank, Kraken 2 is using k=35 as

default.

More often the information will be encoded in the k-mer distribution instead of k-mer size. One classical example is the GC content (it’s a distribution of k-mers with k=1 ), mammals and birds are supposed to have a higher ratio of Gs and Cs to As and Ts, it’s a pattern, not always hold true but it’s there.

Of course, even when working with k-mer distributions the value of K will impact in the kind and quality of information you will be able to extract. A small K will have less information as it just repeats everywhere in your sequencing data a bigger K will be more specific, but if too big, will be hard to define useful patterns due it uniqueness.

With the python function from before we just counted how many times each k-mer appears in our sample (the individual k-mer coverage), the next thing we need to do is generate the frequency of the coverage values:

def calculate_coverage_frequence(kmer_dataset):

_coverage_freq = {}

for coverage in kmer_dataset.values():

try:

_coverage_freq[coverage] += 1

except KeyError

_coverage_freq[coverage] = 1

return _coverage_freq

calculate_coverage_frequence(

{'CTG': 4, 'TGA': 3, 'GAC': 3, 'ACT': 3, 'TGT': 1, 'GTA': 1}

)

This time we get a dictionary that count how many times k-mers with coverage X appears in our sample:

{4: 1, 3: 3, 1: 2}

Plotting this distribution in a histogram is how we are going to run our first k-mer analysis.

Dataset required for this analysis

In this first analysis we are going to estimate the genome size of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis using a whole genome sequencing data generated from Illumina, you can download the reads here and here the link for the run is https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/SRR786188.

Googling for the genome size of Mycobacterium tuberculosis shows that in general this bacteria has a lenght of 4.4Mbp, so if we get a similar number this means that this read data is of good quality and may assembly into a full genome of Mycobacterium.

Step by step guide

The first step is to generate the k-mer count, we are going to use jellyfish for this task. If you like me are running Ubuntu you can easily install this tool by typing:

apt install jellyfish

Make sure to decompress te read files you downloaded from EBI, sadly Jellyfish do not accept compressed read files:

gzip -d SRR786188_1.fastq.gz && gzip -d SRR786188_2.fastq.gz

Generate the k-mer count:

jellyfish count -C -m 21 -s 1G -o output.jf SRR786188_1.fastq SRR786188_2.fastq

Produce the histogram data containing the frequency of kmers coverage:

jellyfish histo -o output.histo output.jf

Next we need to load this data and plot it, here is the code:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

with open("output.histo") as fh:

data = fh.readlines()

dataset = [entry.replace("\n", "") for entry in data]

dataset = [entry.split(" ") for entry in dataset]

def plot_coverage_chart(dataset, min_coverage=0, max_coverage=1000):

coverage = [int(entry[0]) for entry in dataset][min_coverage:max_coverage]

frequency = [int(entry[1]) for entry in dataset][min_coverage:max_coverage]

higher_frequency = max(frequency)

average_cov = coverage[frequency.index(higher_frequency)]

plt.plot(coverage, frequency)

plt.ylabel('Frequency')

plt.xlabel('Coverage')

plt.ylim(0, higher_frequency)

plt.show()

total_number_of_kmers = sum([c*f for c, f in zip(coverage, frequency)])

print(int(total_number_of_kmers/average_cov))

plot_coverage_chart(dataset=dataset)

The first chart is not very easy to read, the first values for coverage have a very high frequency value, and is dominating the visualization, the estimated genome size also seems “a little of” 897 Gbp.

Lets increase the resolution of our port by trimming on the left side, start considering coverage at 7:

plot_coverage_chart(dataset=dataset, min_coverage=7)

This plot is a lot easier for a human to read, and the genome size also lowered

to 82 Gbp, we can brake it down in three to better understand what is happening:

This plot is a lot easier for a human to read, and the genome size also lowered

to 82 Gbp, we can brake it down in three to better understand what is happening:

The red highlight contains the majority of kmers, those are rare k-mers with a low frequency or sequencing errors resulting in unique k-mers, the green highlight represents the backbone of our genome, it looks like a Poisson distribution and that is a great indicator about the health of our data. The third highlight is the repeat tail, the collection of kmers that have high coverage and low frequency, the repeated part of our target genome.

To estimate the genome size we need to make the plot look more with a Poisson distribution, we can do that manually trimming on the sides to generate only the green portion of the plot:

plot_coverage_chart(dataset=dataset, min_coverage=55, max_coverage=250)

This time we get something that looks like a Poisson distribution, and our genome estimation get a lot closer to the expected value of 4.12 Mbp.